Laura Lee Huttenbach/All Photos: Mary Beth Koeth

In 2006, 23-year-old Laura Lee Huttenbach embarked on a six-month backpacking trip from Johannesburg, South Africa to Cairo, Egypt along the African east coast.

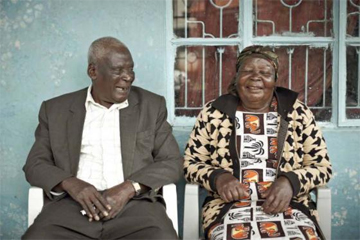

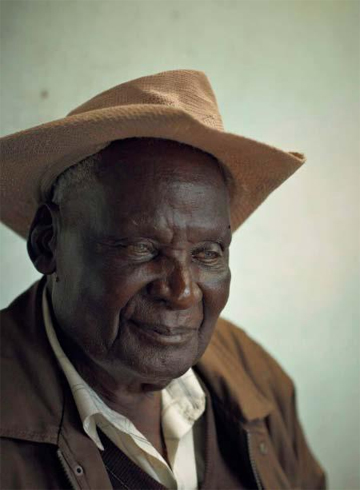

In Meru, Kenya, Huttenbach met Mr. Japhlet Thambu, an 85-year-old tea farmer who went by the name, The General. Thambu had earned the title of General during the 1950s as a leader of the Mau Mau Rebellion, the indigenous Kenyan struggle against British colonial rule.

He talked to her about his experiences as a great-grandfather, teacher, town-celebrity, farmer and a Mau Mau freedom fighter. She lived with the General and his family on their coffee and tea farm for several months, and in that time, The General shared not only his stories, but also his life his home, his family, and his resources. He even adopted Huttenbach as an honorary juju, granddaughter.

From over 100 hours of conversations with The General and more than 1,100 transcript pages emerged, The Boy is Gone: Conversations with a Mau Mau General (Ohio University Press; June 2015). Huttenbach, a Miami Beach resident, will launch the book at the the Coral Gables location of Books and Books on Wednesday, July 15 at 8 p.m., 265 Aragon Ave., Coral Gables.

Q&A with Laura Lee Huttenbach

Q. How did you meet the General?

A. I met the General in Kenya when I was 23, while I was backpacking the east coast of Africa in 2006. Before I left the States, my neighbors introduced me to a Kenyan man named Wilson, who went to church with them. “When you go to Kenya,” Wilson told me, “I want you to stay with my family and teach in our schools.” Then he sent word back to his village that a young American ambassador was coming to visit. When I arrived (dusty and sunburned) in Wilson’s village, his family told me that the General had requested a meeting with me. So we met for dinner at a restaurant called Texas and that’s when we started swapping stories.

Q. Where did the General come from?

A. He grew up and lived in village called Mutunguru, located in Meru, Kenya in the eastern slopes of Mount Kenya, about three hours away from Nairobi. He lived with his wife, Jesca, on their seven-acre tea farm. Their land is fertile and lush. We ate what they grew: Potatoes, kale, carrots, beans, maize and would only buy goat meat from the butcher.

Q. Why is he called the General?

A. He earned the rank of General while fighting in the Mau Mau Rebellion, which was an indigenous Kenyan uprising against British colonial rule in the 1950s that eventually led to Kenyan independence. The General’s real name is Japhlet Thambu, but people addressed him by several titles. For instance, he also went by “Mwalimu,” which means “teacher” in Swahili, or “Chairman,” which came from his executive position at the farmers’ cooperative. Names and titles in the Meru culture mean a great deal.

Q. What was it about the General that made you want to record his life story?

A. First he was a great storyteller. His stories made Kenyan history by extension African history accessible because they were his personal life experiences: How he’d grown up, why he decided to fight against the British, how things changed after independence, and what he’s learned all along the way. He had grown up wearing goatskins and now he put on a business suit most mornings. I wanted to know how that transformation had occurred. He’d also been a primary school teacher his whole life, so he could tell right away if I didn’t understand something. When that happened, he never scolded me for my ignorance but commended my desire to learn. That’s how elders should teach young people. Finally, on a personal note, the General reminded me of my Granddad, whom I was very close to. When my Granddad listened, he listened so intently that his eyes watered. The first time I met the General, his eyes did the same, and it felt familiar.

Q. How has the Mau Mau Rebellion been portrayed in Western popular Culture?

A. The Mau Mau Rebellion has until recently had a pretty terrible reputation in the West. For instance an article in Time Magazine in 1960 described how Mau Mau murdered their victims “by methods ranging from merciful garroting to having their heads bashed in and their brains removed, dried, and ritually eaten.” Stories like this (understandably) stick in people’s minds and when my parents learned that I their last-born daughter intended to move to Kenya to interview a Mau Mau General, they were a little nervous. But they trusted me. Also, in 2005, two revisionist histories of the Mau Mau were best sellers, “Histories of the Hanged” by David Anderson and “Imperial Reckoning,” by Caroline Elkins, which won a Pulitzer. Her work convinced five Mau Mau veterans in 2009 to file for reparations from the British government for injustices during the era.

Most Americans, especially under the age of sixty, have never heard of the Mau Mau Rebellion, but it did come up during the 2012 election, when right-wing politicians and pundits tried to connect President Obama’s paternal side of the family to the Mau Mau Rebellion. (Stephen Colbert actually parodied Mike Huckabee when he “misspoke” on a radio interview: “If you think about it,” Huckabee had said, “his (Obama’s) perspective as growing up in Kenya with a Kenyan father and grandfather, their view of the Mau Mau Revolution in Kenya is very different from our because he probably grew up hearing that the British were a bunch of imperialists who persecuted his grandfather.”)

Q. Why did the General fight in the Mau Mau Rebellion?

A. Before he answered this question, he asked me a question. He said, “When the Americans fought against the British for Independence, what is it they said?” No taxation without representation, I told him. And he said, “That’s right. We had the same in Kenya.” So in the 1940s as a Kenyan man, he had to pay a lot of taxes, but he wasn’t allowed to vote and run for parliament. As a farmer, he was not allowed to use the land how he wanted because the British would not allow Kenyans to grow cash crops like coffee, tea, and timber. He wasn’t allowed to have a beer because alcohol was strictly for Europeans. He couldn’t go to some hotels and restaurants because they were for white people. So all these suppressing factors kept adding up until he said, “Enough,” and took up arms.

Q.Where does the title, “The Boy is Gone,” come from?

A. That was a quote from the General. He was talking about a traditional rite of passage for Meru boys, which culminated in circumcision at age sixteen. After a period of healing, the boys emerged as men. “The boy is gone,” remarked the General. “The boy has gone with men.” Additionally, the white settlers used to call their Kenyan laborers “boy,” no matter the age. After independence, the General noted, Kenyans demanded to be addressed more respectfully. “We said, ‘Why don’t they recognize us as men, and we recognize them as men?’” The title also addresses this great theme of transformation from traditional to modern and coming of age from youth to adult.

Q. In your introduction, you say, “I felt like a piece of my understanding of world history had been missing before I met the General. He put it in place.” What does that mean?

A. When I studied the Second World War, lessons focused on Pear Harbor, Japan, and Europe. When the General told me that many of his agemates were sent to fight with the British against the Japanese in Burma, I was surprised. In fact 75,000 East African soldiers fought in the Fourteenth Army (known as the “Forgotten Army”) in the Far East. In the West, we study history from our perspective, and the General shared another. “When things of history are spoken,” he warned me, “Be careful.”

Q. How did you decide to present it as an oral history?

A. I didn’t think I could improve on the way he told his stories. I wanted the General to speak for himself and preserve his voice so that it is recognizable to his family and his community.

Q. Where did you live when you were interviewing the General?

A. I lived with the General’s son’s family on their coffee farm, about three miles down the hill from the General’s tea farm. Early in the morning, after a breakfast of sweet potatoes, I would ride on the back of a boda-boda (a motorcycle) to meet the General. His granddaughter, Winnie, had just graduated from high school and helped me do things like wash clothes without a washing machine. She also kept me updated on American pop culture. Once, after returning from a long day of interviews with the General, she asked, “Did you hear Rihanna’s getting back together with Chris Brown?”

Q. What was it like living in a rural village in Kenya?

A. It was wonderful, though I use that word as the General uses it, which has a lot of meanings literally, “full of wonder,” but also great, strange, rewarding, and challenging. I’ve never been so aware of being white, and I think that’s an important experience to have, to be the minority. And oh my gosh, water! The fact that in America we can drink the water that comes from garden hoses is the most amazing thing in the world.

Before I left the States, people would tell me, “Oh you’re going to find the best running partners in Kenya,” because they thought all Kenyans ran marathons. I lived in an agricultural village where the idea of burning energy for the sake of burning energy is just stupid. So I was the crazy white girl, running the hills for no particular reason, while they used their energy for productive purposes like planting or harvesting. I was okay with that.

Q. Why did you originally want to travel in Africa?

A. I wanted to go to Africa because I didn’t have a good sense of that continent. Sure, I’d taken classes and I had read articles in the New York Times and National Geographic, but I couldn’t imagine what it was like to live in a country like Kenya. I couldn’t imagine what it was like to live without running water or electricity and to eat only what came from the farm. And I didn’t know what I would have in common with people living in such different conditions from how I grew up. After I graduated from the University of Virginia, I went to teach English for a year in Brazil and while there, my friend who was doing Peace Corps in Lesotho (a country inside of South Africa) called and said, “Do you want to meet me here and then we can backpack together?” I said sure.

Q. Was Africa what you expected?

Japhlet Thambu, The General

A. I didn’t know what to expect. Africa is a landmass that is more than twice the size of the United States, and it is a diverse place in terms of landscape, people, language, and government. When I first arrived in Lesotho, in Southern Africa, it was freezing really, there was snow. The only animals I saw were cows and chickens. Then I went to Mozambique, which had some of the best beaches and best diving I’ve ever seen. Then there was Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Egypt all countries that had unique highlights and challenges.

Q. How do you think Africa is portrayed in Western Media, and how did the General challenge those stereotypes?

A. Our media throws so many strange, sad, and scary images at us from the continent.. From headlines of the New York Times, you see poverty, corruption, genocide, violence, civil war, starvation, and disease (AIDS, Ebola, malaria). Then you also see these noble, wild animals zebras and lions and elephants but even those are getting picked off by poachers. My professor of African history at the University of Virginia once said, “To most American college students, Africa is a vast, unknown, and vaguely threatening void.” My book allows the reader to spend a lot of time with a wise man from Kenya, who wants to be understood for who he is and not where he comes from yet of course he is shaped by where he grew up, as we all are. The General offers a fresh, unique perspective. The great Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in her Ted Talk says, “The problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.” So it’s good and fair to have a lot of stories, and I can’t wait for people to “meet” the General.