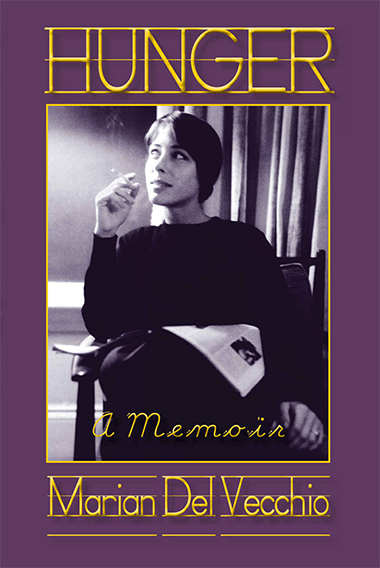

Verve and wit – and a great deal of intelligence – have been the hallmarks of Miami Beach community activist Marian Del Vecchio. Those privileged and proud to know her – and, full disclosure, I am one of them – absolutely know this.

This memoir centering upon the time Marian – then Marian Seidner, the child of Czechoslovakian parents who escaped the Holocaust horror in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s –spent at two different mental institutions in the early 1960s endeavoring to cope with an eating disorder that at the time baffled mental health professionals, is harrowing. Truly chilling in that the “treatment” at the first, McLean Hospital was basically to restrain her movements to the McLean campus, i.e., locking her up, though in an attractive, affluent setting.

Marian writes that the “talking cure” therapy of Sigmund Freud was sorely lacking when it came to treating patients like her at that time, those who were plagued with eating disorders. She says of her treatment at McLean: “We were being pampered in a never-never-land of Freudian hogwash…. Although talk therapy undoubtedly is helpful to the troubled, it has, in my experience, never by itself cured a member of the mentally ill…Too much money changed hands.”

I was reminded of the popular Winona Ryder film, "Girl, Interrupted," also set in a mental hospital in the 1960s. Like Marian, the Winona Ryder character found herself in a place where she truly did not belong, among some very, very mentally ill people. Marian writes with a searing wit and intelligence, even as she describes some terribly sick individuals, the loss of her freedom, and the incompetence of mental health professionals. Do they “cure” her? No. And they didn’t seem to have a very high rate of curing others, either.

But,Marian did not have an altogether bad time at McLean. She starred in a musical that the patients produced and she says she made great friends and even had a romance. There are people who can see the best in situations others would find horrible, and she is definitely one of them. (This is something that so endears her to her friends.)

After a year, released from McLean, Marian goes back to her old life in Boston. A new job, a new beau, but still the bingeing and vomiting persists. Her parents, upon the advice of a new doctor who seems to know something about eating disorders, urge her to enter the Psychiatric Institute, attached to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in Manhattan, for another try at subduing her condition. With her fiancé, Frank, she agrees to go, but not for more than another year.

She describes the pared-down PI, so different from the affluent campus of McLean:

“If McLean was Ivy League, this place is Blackboard Jungle. Forget tennis courts, private rooms, manicured laws, or eminent poets. PI is a stone building in uptown Manhattan, at 168th Street. Symbolically enough, my floor is below street level; one has to take the elevator down.”

Her description goes on: “My floor: off a long corridor are two sleeping areas, a TV room, a dining room and a small nurses’ station. Frills: a bench in the corridor, bureaus and cots in the sleeping areas, long tables and chairs in the dining room, a couch and some chairs in the TV room.”

Unlike McLean, the men’s ward is totally separate. McLean had mixers where male and female patients could meet. PI is a horse of a different color. And the locking up is even worse: “There is no way of knowing what the weather is like, or pretty much anything else going on in the outside world.”

Does it sound like a prison? I’d say so.

She states that her days on the ward “aren’t exactly thrilling” and only broken up by playing volleyball on an upstairs floor. She’s prescribed a nutritional drink to try to bring up her weight. It doesn’t. She makes friends, as she did at McLean, and participates in, in addition to volleyball, occupational and psychiatric therapy. She likes the doctors here much better than she did at McLean…they are not the Freudians she encountered in her first stay in a psychiatric hospital….but do any of them have answers for her, for why she is still bingeing and purging, getting food from the outside from other people? Not really.

A high point for her is volunteering to be a case study for Hilde Bruch, the doctor who recommended the PI to Marian and her parents. In it, Marian posits what she herself believed to be the most important causes of her illness: “Being a twin and the war.” Her relationship with her identical twin, Susan, with whom she tended to compare herself unfavorably, she felt, was key, as was her troubling relationship with her extremely supportive parents. She later comes up with what she thought could be another cause: genetics. Her maternal grandmother, her aunt, and two of her uncles all committed suicide.

But the days drag on, and she has to admit to her fiancé,“I’m still as bad as ever.”It’s the fall of 1964, and the year committed to the PI is up. The psychiatrists do not want her to leave, but she is a voluntary patient and they cannot keep her there. Her doctor insists that she is “not ready” but her discharge papers stated that she was released as “improved.” The diagnosis was “Psychoneurosis, Anorexia Nervosa,” and she was discharged “to self.”

This is a compelling story and not one with which most of us is remotely intimate. It took courage to write such a memoir and it is inspiring to read it. It was a major challenge for Marian Seidner to overcome this painful eating disorder and to share her experiences with others. She credits Frank Del Vecchio for his staunch, no-nonsense support, and, yes, she got better. She became a wife, mother to two children, and a participant in the Del Vecchio family business and community activism. And we are all the better for it.

The postscripts are sad. Several of those with whom she was most friendly at these two psychiatric hospitals committed suicide; but others survived and did well. She was in touch with Hilde Bruch until the doctor's death in 1984 and she appears in her book, "Eating Disorders," under another name. (Note, too, that the names of the psychiatric patients with whom Marian Del Vecchio interacted are all fictitious.)

Well done, Marian, well done.

The book, "Hunger: A Memoir" is available at the Miami Design League Gift Shop and also through Amazon.com at www.amazon.com/HUNGER-MEMOIR-MARIAN-DEL-VECCHIO/dp/1793868980