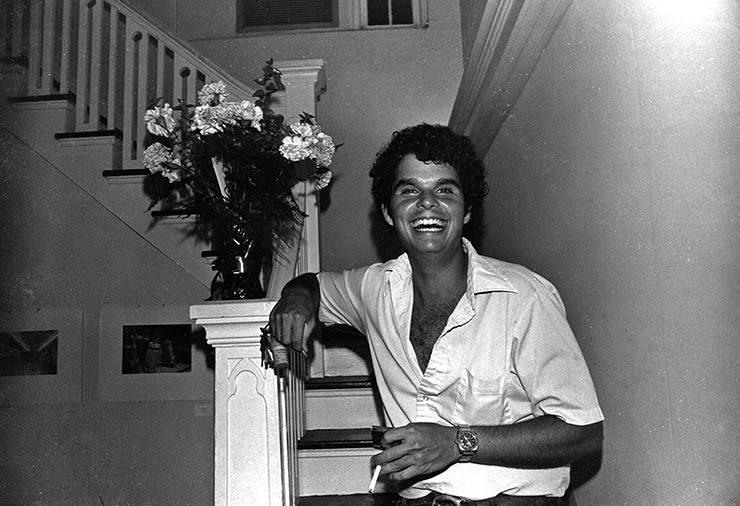

Photo by Andy Sweet (courtesy Kino Lorber)

Their smiles are frozen in time, a reflection of extended leisure as a way of (retired) life. Contentment, easygoing repose and unbridled joy converged in the photographs of Andy Sweet in vibrant, saturated hues, crystallizing their subjects of a certain age with a disarming spontaneity. It's almost as if the artist and his subjects were in cahoots. Their mission? To persuade the viewer to join the party, blissfully unaware as they were that the festivities were coming to an end much sooner than expected.

“The Last Resort,” a new documentary from local filmmakers Dennis Scholl and Kareem Tabsch, aims to chronicle the days of South Beach as a sleepy retirement community where Jews, many of them originally from Eastern Europe, got away from the big-city noise and frigid weather up north to be a part of their own tropical playground. It also pulls double duty as a portrait of Sweet, who, alongside friend and fellow shutterbug Gary Monroe, were determined to capture this community before it faded.

Photo by Gary Monroe (courtesy Kino Lorber)

All the elements for a nonfiction home run are in place. The interview subjects are on point: Monroe joins journalist and true crime writer Edna Buchanan, Jewish historian Susan Gladstone, Books & Books owner Mitchell Kaplan, Miami-bred filmmaker Kelly Reichardt (“Certain Women,” “Wendy and Lucy”), Sweet's sister, Ellen Sweet Moss, and his brother-in law, Stan Hughes. There's a wealth of archival footage and vintage TV news reports, suggesting the directors did their homework and wanted to get everything just right. Then, of course, there are the jewels in the crown: Sweet's playful snapshots, which seem to radiate joie de vivre from within without ever coming across as pretentious.

It's a lot to pack into 70 slim, tightly constructed minutes. And yet the film, which strolled away with the Audience Award after making its world premiere at the 2018 Miami Jewish Film Festival, unfolds in perfunctory, matter-of-fact fashion, boxing in its subjects into a dispiritingly ordinary talking head format. Scholl and Tabsch have made a documentary about a magical time and place that is itself conspicuously low on magic. The impish glee that made Sweet's work, as well as the people in front of his lens, so special is something that remains just out of their reach.

Photo by Andy Sweet (courtesy Kino Lorber)

Part of the problem lies in the filmmakers' general-summary approach to oral history, their decision to let their interview subjects do the heavy lifting in terms of narrating Miami Beach's evolution, when they should have been asked how said changes affected them. Gladstone, and to a lesser extent Buchanan and Kaplan, discuss the city's transformation, but their descriptions are mostly flavorless and surface-deep.

The end result often feels like a dry history lesson, characterized by a dearth of personal accounts. It's telling that the most memorable moment, shared by Gladstone, is one such anecdote, involving a welfare check on an elderly woman, made all the more effective because it describes a specific encounter rather than making an overarching observation. For a bittersweet minute, the sense of loss and loneliness these retirees felt when their South Florida paradise eroded into a crumbling purgatory brings the movie to life.

Sweet remains an engaging subject throughout, but the film is juggling so many elements that he's too often relegated to a supporting player in his own story, ceding into the background when he ought to be taking center stage. Scholl and Tabsch etch the photographer's childhood and adolescence in broad strokes. They contrast the chasm in sensibilities between his candy-colored work and Monroe's somber, meticulously composed black-and-white images. But Sweet remains a bit of an enigma, something that is further complicated by the movie's timid handling of his personal life. The film walks on eggshells around the notion that Sweet was believed to be gay. It treats the issue in discreet whispers, so as not to cause discomfort to a demographic that might have taken issue with a more frank depiction. This tiptoeing deprives “The Last Resort” from exploring the queer sensibility in Sweet's work, and it's here where the film truly feels like a missed opportunity.

Andy Sweet (courtesy Andy Sweet Photo Legacy)

Even more problematic is how it lumps together talk of Sweet's sexual orientation and his descent into drug use and rumored cocaine dealing. There's an undeniable narrative pull to the film's foray into the crime wave that took over Miami in the wake of the Mariel boatlift, leading to a sobering hard-news approach to Sweet's untimely death at age 28 in December 1982. (Think of a Rakontur production, only more nondescript and impersonal.) But despite Scholl and Tabsch's clear-eyed look at Sweet's violent demise (“It was Andy that got Andy killed,” observes Monroe), they take an antiquated, astonishingly backwards angle on his extracurricular activities as a “lifestyle.” It's pretty evident the parallel is unintentional, but the filmmakers do not make enough of an effort to separate Sweet's sexuality from his personal demons.

To their credit, they also refuse to shy away from the long-lasting clashes between Monroe and Sweet's family after his death about what to do with the work their loved one left behind. But asking the subjects thorny questions is more the exception than the rule here. Equally lamentable is the limited screen time alloted to Hughes' decade-long efforts to restore Sweet's body of work, much of it thought lost after the negatives were misplaced, to its former splendor. The closing montage, showing the restored prints, underscore how the photographs transcended time-capsule appeal to reach something more timeless and universal. They also hint at the movie that could have been.

Photo by Andy Sweet (courtesy Kino Lorber)

You won't get an argument from me if you contend “The Last Resort” covers an important chapter in Miami-Dade history. It does. Don't let this crabby critic keep you from going out and supporting local filmmakers. But as you sit through this underachieving crowd-pleaser, ask yourself, should such fascinating subject matter be pared down until it resembles a glorified study aid? Does it truly do justice to Sweet's legacy?

“The Last Resort” is now showing at Coral Gables Art Cinema and O Cinema Miami Beach. It's scheduled to open at the Miami Beach Cinematheque March 1.