Photos by Brittany Mazzurco-Muscato for Florida Grand Opera

Someone once said the second most popular theme for storytellers (the first being love) is the Holocaust. What quickly comes to mind is Cabaret, The Sound of Music, The Producers, The Diary of Anne Frank, Sophie’s Choice, Schindler’s List – and the list goes on and on.

As well, compelling stories tend to morph from one medium into another.

When a radio play becomes a novel which becomes a film and then an opera, it has some serious legs.

While visiting Paris several years after the war ended, Polish writer Zofia Posmysz, survivor of Auschwitz, overheard a German woman yelling at a group of German tourists. This triggered a deeply painful memory in Posmysz’s mind and inspired her to create a radio drama, Passenger from Cabin Number 45, which put an authentic spin on her compelling autobiographical fiction, the story both disturbing and possibly redemptive at the same time.

Posmysz adapted her 1959 radio play into the novel, Pasażerka, on which Andrzej Munk's film and Mieczysław Weinberg's opera, The Passenger, are based.

Mieczysław Weinberg? Perhaps the most famous unknown Soviet composer of our time was a Polish-Jew who, after graduating from the Warsaw Conservatory in 1939, left Poland to escape the imminent Nazi occupation. He wound up in Moscow, losing his parents and sister in the Holocaust.

Weinberg, whose prodigious output includes many symphonies, string quartets and film scores, was prompted by Dmitri Shostakovich to write The Passenger, later hailing it as “a perfect masterpiece.”

The opera is a shadowy metaphor of sorts; it recalls the darkest period in the modern history of our planet, exhorting us never to forget the atrocities of the Holocaust. Yet, the Soviet Authority prevented the premier of The Passenger at the Bolshoi in 1968 and suppressed it for decades. Weinberg never saw his opera performed.

Photos by Brittany Mazzurco-Muscato for Florida Grand Opera

British director David Pountney uncovered it and staged a premier at the 2010 Bregenz Festival in Austria, igniting a series of posthumous productions. Several productions have since been mounted throughout Europe and in the U.S., including Houston, New York, Chicago and Detroit. And now, Miami.

The Passenger opened at Miami’s Arsht Center under the baton of Florida Grand Opera conductor Steven Mercurio on Saturday, April 2, FGO’s third installment of the company’s “Made for Miami” series.

Alexander Medvedev’s original libretto was in Russian, but the revised libretto would reflect the cosmopolitan languages of the SS and their prisoners – German, English, Polish, Yiddish, Russian, French, Greek and Czech. FGO’s international cast was adept at navigating the polyglot score, with English and Spanish subtitles available for the Miami audience.

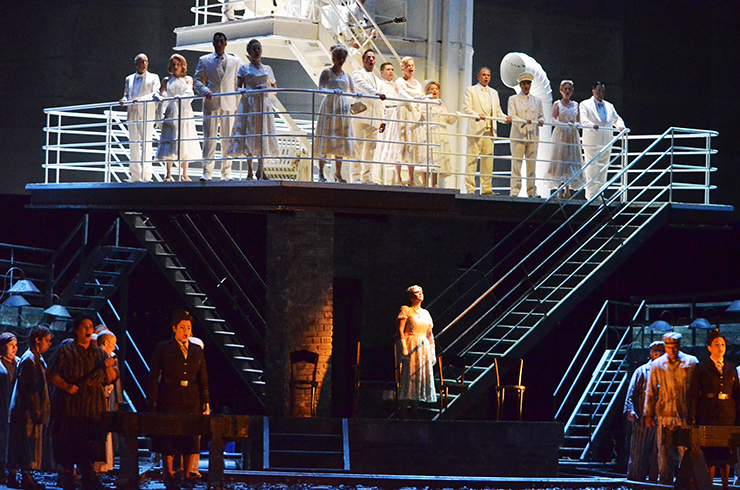

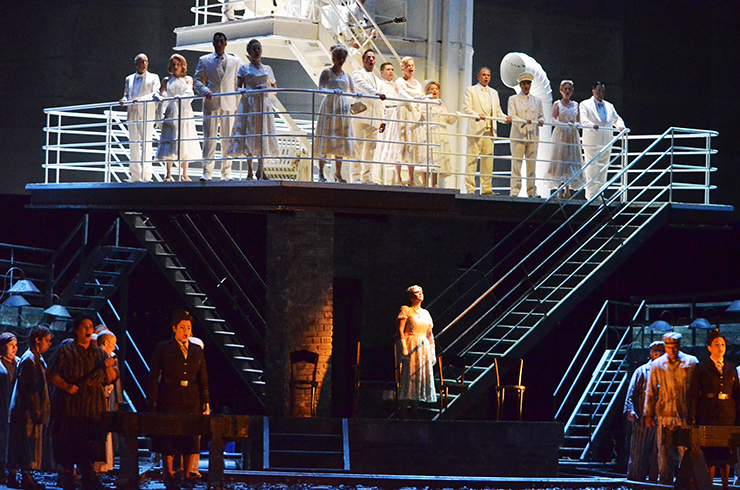

The upper level of Johan Engels’s set consisted of two decks and a smokestack, the top level all gleaming white and representing an ocean liner, counterpoised with the lower deck, a dark, grim, hellish representation of Auschwitz. This allowed the action to move seamlessly between the diametrically opposed worlds of the squeaky-clean present and the forbidding squalor of the past.

Two boxcar like constructions, one on either side, rolled into place in front of the central set when needed to serve as the women’s barracks, or a ship’s cabin shared by Liese and Walter. Watchtowers on either side at the proscenium, manned by soldiers wearing iconic German helmets, illuminated the characters at various times.

What the settings had in common was that they described confined spaces where the characters could not escape facing the reality that each environs presented.

Most of Weinberg’s music in The Passenger is melodic recitative, constantly moving the action forward, perhaps making it more of a theatrical experience than a musical one. He has keen musical instincts; his instrumentation is both minimal, to allow the emotion of the characters and scenes to unfold naturally, and powerful to riveting effect without being melodramatic or schmaltzy. At times, Weinberg employs silence, allowing the "weight of hopelessness" to consume the stage.

Interestingly, the story is told by non-Jewish protagonists.

Photos by Brittany Mazzurco-Muscato for Florida Grand Opera

The story is seen and heard through the eyes and ears of Liese (mezzo-soprano Daveda Karanas), a former SS guard at Auschwitz, returning in her mind to “relive” the horrific events which she unsuccessfully tries to justify.

Karanas, played the regal fashionable wife of the West German diplomat, Walter (tenor David Danholt), as well as the imposing guard in her tailored officer’s uniform. Danholt was the picture of self-righteousness and rectitude. All the main characters possessed good acting chops and voices to match.

Pounding timpani, dissonant chords, a cacophony of winds and frenetic strings set the mood. When Liese, en route with Walter to a new diplomatic post in Brazil, noticed a mysterious veiled woman on deck, the dramatic action was launched.

Danholt’s unblemished tenor and Karanas’s expansive mezzo blended well into their characters. Their reticence at the ship’s rail, belying their words of love, contrasted effectively with their torrid physicality toward each other during Walter’s first learning of Liese’s past life as a guard at Auschwitz.

The music became subliminally creepy when Liese first noticed the veiled woman as possibly her prisoner Marta (soprano Adrienn Miksch), whom she sent to a certain death. Rising percussion against dissonant strings followed the disturbed Liese retreating to her cabin. A frenetic marimba accompanied Karanas broad mezzo, loaded with emotion as she contemplated the horrifying possibility of Marta being alive and on deck.

Percussion, big horns and trumpets sounded as Walter confronted Liese, attempting to justify her actions at Auschwitz (“I was just following orders…”). Their strong voices with the recitative and the overwhelming music resolved as Walter tried to understand, the music becoming minimal, but foreboding.

Once the steward, character bass Tony Dillon, announced that Marta was British, a jazzy sax and clarinet signaled relief in the pair.

Solo bassoon and tuba joined a slight oom-pah band as several SS officers (bass-baritones Alex Soare and Zachary Elmassian, and tenor Daniel Bates) ruminated on how they “cleanse the earth for the führer” and how “human extermination is a science.”

Several scenes featuring the women prisoners, their shaved heads, vestigial appearance and striped rags, crawling and retreating into their small bunks, were disturbing and moving, especially in contrast to the snappy white outfits of the robust passengers dancing on the ship’s deck. The SS guards and officers wore crisp uniforms, while the male choir, observing and commenting like a Greek Chorus, were dressed in dark contemporary suits and ties.

Photos by Brittany Mazzurco-Muscato for Florida Grand Opera

No gruesome details were spared – the brutal beating of the Russian prisoner Katja, thickening smoke during the Auschwitz scenes, prisoners coming with shovels and wheelbarrows to remove ashes from the crematorium – all on stage.

Inside the death camp, Marta, gamine but resolute, soared lyrically as she wondered why Liese (now her overseer) was staring at her, what she wanted from her, and if she had any humanity.

Miksch rendered a defiant yet beautiful aria as the women surrounded her for her birthday. Her soprano was strong and round, singing “when the sun has sunk without a trace, I’ll know death is near…” After caressing her money note and an orchestra crescendo, a solo cello deepened the mood.

Each female prisoner had a fully realized character, each with their own dream of freedom. A standout was soprano Anna Gorbachyova, playing the tall, frail Katja. After a tense confrontation between Liese and Marta, breaking the tension with a wonderful Russian folk song, Gorbachyova’s voice was as light and soft as it was expressive with the pretty a cappella aria.

Marta’s fiancée Tadeusz (John Moore) applied his warm baritone as the lovers met for the first time in two years – “my pretty Marta, my sad Marta,” ringing true to her embarrassment for her poor appearance. Tender strings underscored their exchange of memories, Miksch’s sweet soprano full of dimension as she asked him to play his violin like he did years before when they were together in the choir loft.

Moore’s baritone was both lyric and strong as he defied Liese’s offer to arrange for a rendezvous with “the famous Madonna of the Barracks,” refusing to be in Liese’s debt, his physical defiance as imposing as his vocals.

As they confronted each other, Miksch and Karanas’s powerful voices combined forcefully as Liese tried to bribe Marta with a promise for her to see Tadeusz. She refused.

It was up to us, the audience, to decide how cruelty and despair, and defiance and courage could coexist in equal measure.

The men’s chorus, commenting with a collective voice, maintained an ominous presence, warning “the gates of Auschwitz turn only inward…the pitch black wall of death…the will (to survive) lives in the darkness of hell.” They watched the scenes as if to memorialize what they observed.

When the steward returned with the news that the mysterious passenger was reading Polish books, Liese tried to cast off doubt by dancing (a bass, piano and accordion combo on the upper deck, playing a little jazzy number) until the veiled woman in white handed a note to the band, requesting them to play the cheesy waltz that the commandant of the camp favored. The die was cast.

In a nifty bit of theatrical craft, the veiled woman backed Liese, in her party dress, down the stairs from the ship’s deck into the death camp, merging the present with the past, forcing Liese to emotionally blend the two dissimilar worlds as she witnessed the concert where Tadeusz played the Commandant’s Waltz.

In a final act of defiance, Tadeusz, with bravery and resolve in the face of unfathomable choices he must make, opted not to play the commandant’s favorite waltz music, but instead played the Bach Chaconne in D Minor. With Moore’s back to the audience as he played, FGO’s Franz Felkl soloed the Chaconne. Ominous chords from the orchestra consumed the Bach, Tadeusz’s violin was smashed and he was dragged off to his death.

An epilogue was played in front of a metallic curtain, the ship and camp no longer in view.

Marta appeared tastefully dressed in a tan skirt and blue sweater, immaculately groomed, with beautiful, well-coiffed hair. It was a shock for the audience to see her so completely restored to health and normalcy.

Photos by Brittany Mazzurco-Muscato for Florida Grand Opera

Kneeling in her party dress, bearing witness upstage of Marta, Liese was now inanimate, chastened and defeated. She could no longer justify her past actions; she could no longer refuse it or dance it off. Marta and Liese had switched roles.

Marta now determined that the voices of the dead would never be forgotten, sang a lament, remembering the women from the camp, and most deeply, Tadeusz. Marta’s voice trailed off into softness, the lament concluding with a hopeful chord.

She and the other survivors were, of course, the worst nightmare of all those who “served” at Auschwitz. Perhaps this role reversal, victim becoming overseer, guard becoming victim, was a catharsis for the author and composer. And perhaps for us as well.

One could only remember and hope for some feeling of redemption.

The Passenger

By Mieczysław Weinberg; libretto by Alexander Medvedev; conductor, Steven Mercurio; stage director, David Pountney; associate director, Rob Kearley; production, Bregenz Festival; sets by Johan Engels; lighting by Fabrice Kebour; costumes by Marie-Jeanne Lecca; chorus master, Katherine Kozak; assistant conductor, Michael Sakir; musical preparation by Tessa Hartle; production stage manager, Liam Roche; FGO general director, Susan T. Danis; adroit observations by Justin Moss.

CAST: Adrienn Miksch (Marta), Daveda Karanas (Liese), David Danholt (Walter), John Moore (Tadeusz), Anna Gorbachyova (Katja), Kathryn Day (Bronka), Elena Galván (Yvette), Eliza Bonet (Krystina), Hilary Ginther (Vlasta), Agnieszka Rehlis (Hannah), Alex Soare (SS Man 1), Zachary Elmassian (SS Man 2), Daniel Bates (SS Man 3), Robynne Redmon (Old Woman), Tony Dillon (Older Passenger/Steward), Géraldine Dulex (Kapo/Overseer).

SCHEDULE | The Passenger

Sung in multiple languages with projected translations in English and Spanish

Miami Adrienne Arsht Center / Ziff Ballet Opera House

April 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 2016

Tickets are available at the Arsht Center website (www.arshtcenter.org) or by calling the box office (305.949.6722).

www.fgo.org