If dreams can be analyzed to reveal the complexities of our unconscious selves, can cowbells represent dreams? South Florida audiences tuned into that possibility on March 6 and 7 at the Knight Concert Hall when The Cleveland Orchestra presented Mahler Symphony No. 6 ("Tragic").

Franz Welser-Möst, TCO's principal conductor, made his argument that psychoanalysis was catching on in European society at the turn of the 20th century, and that Mahler during that time explored his conscious and unconscious mind for material for his 6th Symphony. Welser-Möst maintained that symphonic works up through the late Romantic period were firmly rooted in the outer 'physical' world and that Mahler mined his inner world for creative inspiration.

Not every great conductor is a great composer. Mahler was both. He helmed the Vienna Court Opera, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic and completed 10 symphonies. Not too shabby. His œuvre is small but his works are large.

So, if the 6th Symphony is a Journey through Mahler's subconscious, a little housekeeping may be in order.

It is unclear if the "Tragische" nickname came from Mahler, or if he nicknamed it thusly and later withdrew it. Regardless, the cognomen proved something of a misnomer – while he was composing the 6th, he had a pretty wife, a second daughter on the way and money in the bank from royalties and as director of the Vienna Opera. Next, regarding the two middle movements, whether you like the andante before the scherzo or the scherzo before the andante (Mahler had it this way originally and then reversed the order), it's all good. Finally, Mahler originally included three gigantic hammer strikes towards the end of the fourth movement (three mighty blows of fate?), removing the third one in later revisions. Some conductors like to put the third one back. Two or three? Again, it's all good.

Now, to the work. Music speaks louder than words. When exploring dreams, fears and beauty, words can be woefully inadequate. Mahler's 6th is an immense work with sinister visions, nihilistic moments, rabbit holes, sumptuous melodies and boundless beauty. To position this work as simply "tragic" is well, tragic. It's so much more.

In his 6th, Mahler connected the dots between sorrow and joy, pleasure and pain, with wonder as its connective tissue. It is a landscape of searing figures, heavenly moods and a non-stop flow of contrapuntal invention. He brought together numerous musical ideas in infinite combinations, accomplishing this in part by taking a cue from Wagner and assembling orchestral ensembles as large as the stage could hold.

Mahler's 6th established dark and light elements from its onset. TCO marched the audience steadily into and through an ominous wall of sound in the first movement, the "fate" motif yielding to a hymn-like segue which morphed into a beautiful soaring romantic theme expressed vividly by the winds and strings. After luxuriating with the gorgeous music, it was back to the muscular cadence, every section of TCO involved.

Mahler favored percussion to detail his big music. In all four movements, percussion was assigned to punctuate – hard driving drums like marching steps, a tingling celesta as a brief respite from the brewing mayhem, jingling bells, triangle, xylophone, cowbells (really!), tam-tam, glockenspiel, and twig brush to lighten up emotional weight.

Trumpets blared, drums pounded, strings calmed and the orchestra awoke from the dream – the musical back and forth was loaded with expanse and vitality, landing with the romantic theme layering brass, strings, winds and percussion.

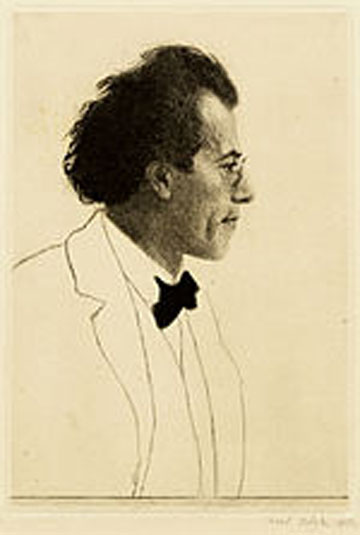

Gustav Mahler, circa 1902

The slower movement (andante) was a breather from the force of the rest of the work. Serene strings brought a soothing theme, a mood changer, conveying a quiet state of floating to the hall. The wistful melody was taken up by solo brass, wind and string instruments as well as full sections throughout the movement. Every player in TCO seemed to work their way through the trance with divine concentration. The strings repeatedly suffused the entire orchestra as the melody grew in all directions, never losing its shape. A distant horn was heard, the strings rose in ecstasy, the orchestral sections folded in on top of each other, falling and mounting beyond physical boundaries, the winds sustaining a chord as the bottom put a delicate button on it

The scherzo returned to the pounding rhythms, starting out big and growing bigger, suddenly dissolving into a lighter theme, an oboe and bassoon engaging in a playful interchange. Irregular rhythms tossed between individual instruments and full orchestra, sounding at times almost like a lumbering giant. Percussion again garnished the main event – xylophone here, triangle there, individual reeds, flutes and violins poking through the cloud.

Mahler wrote in the score's finale, "part for large hammer." The head of TCO's hammer was a foot wide and the handle several feet long, certainly sufficient to create a "hammer blow of fate."

Many forces converged in the final movement, characterized by sweeping mood changes from splendid spiraling melody to unfathomable anguish.

What might have blossomed as romantic quickly turned dark as a brief harp and string reverie dissolved into the lower brass and lower winds. Tuba (Yasuhito Sugiyama) took a mysterious turn, the lower voices creeping alongside and becoming a chorale. TCO forged ahead, built and swelled into a quirky little bounce with something lurking in the shadows. Every section fought for its space, the romantic theme emerged and bloomed in the strings, and the first hammer dropped. Trumpets blared, the orchestra returned to the pounding cadence, the points of sound again took us down the rabbit hole, and the second hammer dropped. Voices clashed and counterpoint ruled the stage. The harp influenced a new mood, Sugiyama's tuba wandered in, and earlier themes were expressed and exploded. In the throes of the ending, the tuba angled for resolution with the trombones and horns in quietude; one big blast and it was over.

Mahler removed the third blow, perhaps to forecast his own death, but not until he thankfully wrote four more symphonies.

Pressure makes diamonds, and the pressure of invention kept the audience engaged for this 75 minute work. Excessiveness was kept at arm's length due to the unending resourcefulness of Mahler's mind and the interpretive skill of TCO. It is rare to sign up for a concert with only one work on the program. Not that the programming director couldn't include another short one before the Mahler, but that Mahler's 6th tends to be all any listener needs to get their music fill.

A child who didn't learn to play together with other children probably did not grow up to be one of these remarkable TCO musicians. The 100 plus players moved precisely together, completely in sync under the baton of maestro Welser-Möst. The conductor's unruly crop of salt and pepper hair, constant and fluid arm and friendly smile built a captivating visual, as he communicated and connected with each soloist and section of the orchestra.

At its conclusion, Welser-Möst presented each section and soloist (Sugiyama a fave), the players all receiving a well-deserved ovation.