"The Boy and the Heron" is playing in theaters in subtitles as well as an English dub featuring the voices of Robert Pattison, Florence Pugh and Christian Bale. (Photo courtesy of GKIDS.)

The flames are a blur of orange and crimson. Ashes rain down like soft feathers. And, as hope peters out like dying embers, a boy's molting period begins.

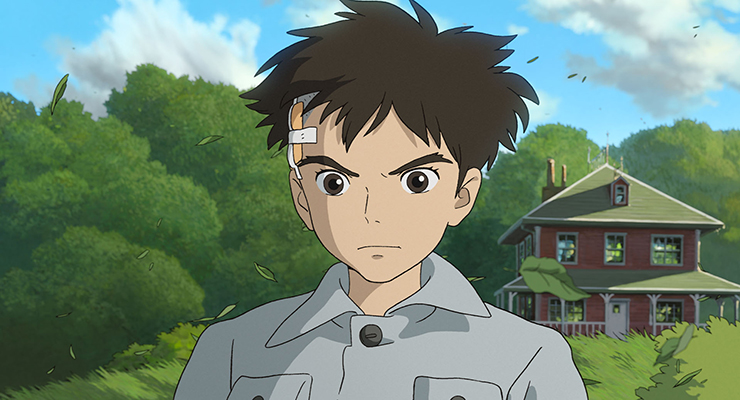

The year is 1943, and as “The Boy in the Heron” opens, a 12-year-old boy with piercing brown eyes named Mahito dashes past terrified passers-by as he runs toward the burning hospital in Tokyo where his mother Hisako works. The frightened onlookers morph into one another, and a tower of fire shoots up into the sky, Hisako's face blended in with the inferno, as the air raid sirens blare incessantly.

Those expecting “Heron,” the twelfth feature directed by Japanese animation wiz Hayao Miyazaki and his first in a decade, to be the usual gallery of fluffy cumulus clouds, cuddly creatures and pastoral flights of fancy are in for a bit of a rude awakening.

The 82-year-old has come out of retirement to make a somber, fiercely felt meditation on loss and its ripple effects, inspired by his own childhood. It's a wrenching and dense work of art, a philosopher's fantasy film. It is also a ripping yarn that unfolds like a graphic novel you can't bring yourself to put down.

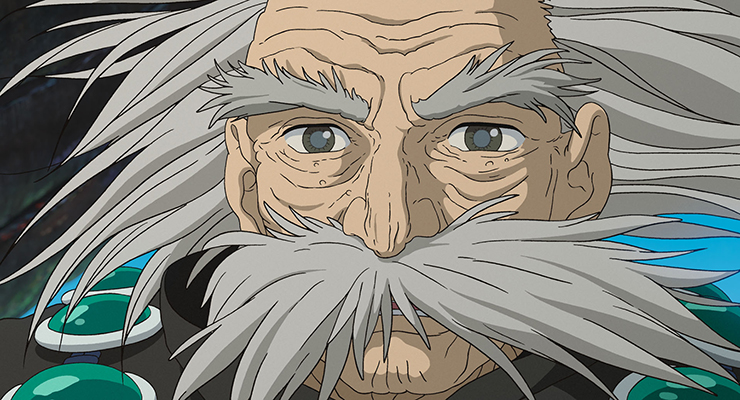

The filmmaker has been known for his hand-drawn animation, sticking to old-school, painstaking frame-by-frame methods. "The Boy and the Heron." (Photo courtesy of GKIDS.)

The message is clear when it comes to the film's startling first scene: losing a parent is a living nightmare. The loss of a loved one while a country is at war gives an added collective dimension to the pain. In the aftermath of the deadly blaze, Mahito's father Shoichi, an air munitions factory owner, marries his sister-in-law Natsuko and moves Mahito to her estate in the countryside. Natsuko is warm and cordial, and her maids, introduced as an undulating wave of oversized wrinkled faces, try their best to make the withdrawn new arrival feel at home. Dad, meanwhile, is MIA, a workaholic who leaves his son to his own devices, as the shadow of war looms large over all of them.

There are echoes of “Bambi” in Mahito's predicament: a mother who meets a violent fate and a cold and distant father. But this is as far from Disney as Miyazaki, nicknamed the Japanese Walt Disney many moons ago, has ventured. A much closer parallel is Guillermo del Toro's “Pan's Labyrinth,” in the way both auteurs blend fantasy and real life during wartime to lyrical effect.

"The Boy and the Heron" is the twelfth feature directed by Japanese animation wiz Hayao Miyazaki and his first in a decade. (Photo courtesy of GKIDS.)

Miyazaki takes his time showing Mahito's inability to acclimate to his new home. There's a raw and unvarnished quality to the way the filmmaker portrays his protagonist's struggles to cope. The film's Japanese title roughly translates to “How Do You Live,” and there's a visceral charge to its matter-of-fact depiction of the boy's despair. (This is a film of spiky edges. Parents, take the PG-13 rating seriously.)

There are mysteries underneath the placid rural surfaces, starting with the titular bird that periodically pops up. An enigmatic messenger that appears to dare Mahito, the heron's prodding triggers a quest that will take the boy to an abandoned, boarded up house that, like the heron himself, is not quite what it seems. This isn't the loopy rabbit's hole that gave “Spirited Away” its transporting kick, but a more grounded portal to other worlds. with outlandish visuals that bring to mind Latin American magic realism before they slide into surrealism.

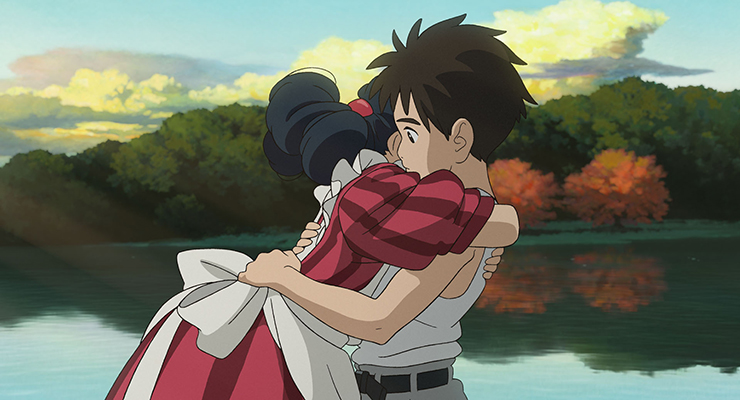

A scene from "The Boy and the Heron." (Photo courtesy of GKIDS.)

A distraction from his grief? Or an opportunity to channel it into doing good? Whatever the reason behind his decision, Mahito takes the plunge after a family member goes missing, opening the door into a myriad realms. The boy is alternately aided and (mostly) thwarted by the heron, a deceitful trickster with whom the boy strikes an adversarial relationship, as he experiences the challenges and pleasures of Miyazaki's idiosyncratic variation on the multiverse. Along the way, he encounters majestic ghost ships, cartoonishly large multicolored parakeets and puffy floating beings that look like distant cousins to “Princess Mononoke's” forest sprites. There is also, it must be mentioned, a realistic amount of bird droppings on display.

Miyazaki's worldbuilding is bracingly byzantine, its particulars barely explained to viewers because he trusts viewers to keep up. It's safe to say there is no hand-holding here. Accompanied by a stripped-down, piano-driven score by longtime collaborator Joe Hisaishi, Miyazaki takes the narrative mold for many of his best-known works, that of a young person confronted with a test of their mettle in an often hostile environment, to make his most mature hero's journey to date.

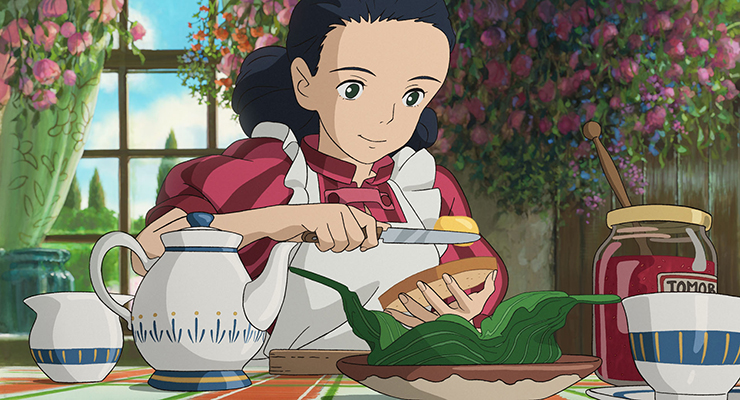

A scene from "The Boy and the Heron." (Photo courtesy of GKIDS.)

Life is a constant battle, but there is also breathtaking beauty, the thrill of discovery and the satisfaction of personal breakthroughs. Miyazaki could have opted to do a victory lap, a nostalgia trip that pays tribute to all the realms he has created from scratch over four decades. Instead, he has wielded his boundless imagination to tell a personal story, at once expansive and intimate, with the vigor and vitality of a filmmaker half his age. He appears to take an inventory of the places he's been, with a possible passing of the torch to the next generation. (But maybe not just yet. He is reportedly working on a new project.)

I have been doing this long enough to recognize a great movie when I see one, and “The Boy and the Heron,” a haunting, admirably tough jewel from a master storyteller, is a great movie. Watch it take flight.

"The Boy and the Heron,” the latest work from beloved Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, has become his first film to top the North American box office. (Photo courtesy of GKIDS.)

“The Boy and the Heron,” the top movie at the North American box office at the time of this writing, is now playing in wide release across South Florida, with showtimes in Japanese with English subtitles (the version that was screened to press), as well as an English dub featuring the voices of Robert Pattison, Florence Pugh and Christian Bale.

MAIN MENU

MAIN MENU