You would assume a program with Copland on one end and Stravinsky on the other would be a savory SANDWICH of music – unless the sustenance in the middle was overgrown.

That’s what audiences bit into Saturday night, Dec. 6, when John Adams helmed the New World Symphony at New World Center on South Beach.

All the fine ingredients were there: the budding NWS orchestra of 84 talented young musicians and the baton of Adams, an accomplished composer and conductor.

Aaron Copland’s El Salón México was a pleasing start to the program. His signature sound with confident strings, dominant brass and clomping percussion, quickly fell into a wonky drunken stupor, with a quirky trumpet (Ryan Darke) sounding like a Mariachi just waking up from his siesta. The audience grazed on a series of popular Mexican tunes (“El Palo Verde,” “La Jesusita” and “El Mosco") embodied in the winds and strings. A laughing clarinet (Ran Kampel) regaled the crowd. The NWS sounded terrific as did the soloists, including bassoonist Sean Maree.

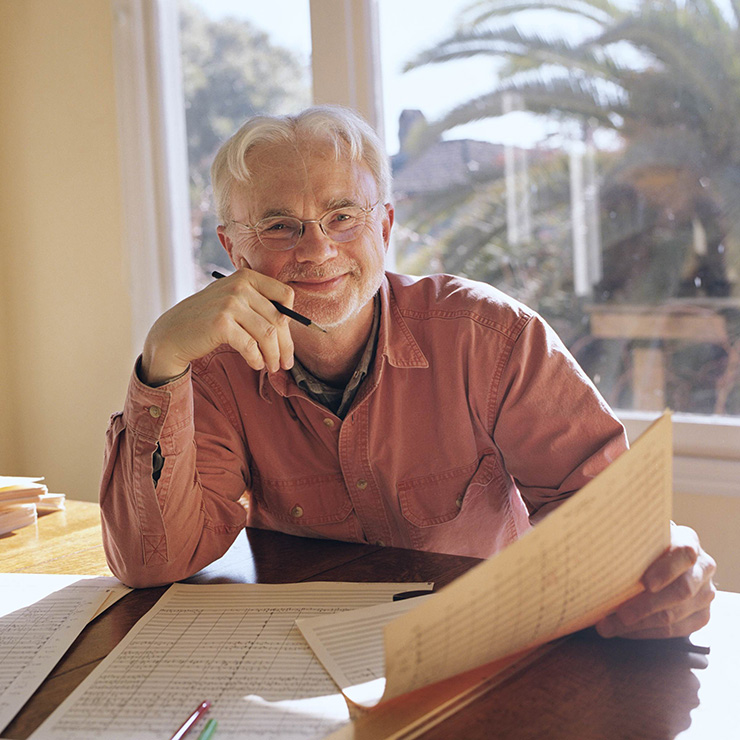

John Adams

Adams, who grew up listening to the saxophone music of Cannonball Adderley, Coltrane and Getz, has a deep fondness for the sound and the instrument. When he learned that Timothy McAllister (the evening’s soloist whose chops are considerable on alto sax) was a performance cyclist, Adams figured McAllister had no fear and wrote a saxophone concerto for him in 2013.

There is no doubt about Adams’s accomplishments as a composer of contemporary symphony and opera (Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic). He has received honorary doctorates from Yale, Harvard, and The Juilliard School and also garnered the 2003 Pulitzer Prize in Music for the Transmigration of Souls, commemorating the first anniversary of 9/11.

So what is Mr. Adams reaching for in his Saxophone Concerto? There are certainly no melodies to hum here. In fact, watching Mr. McAllister tool around on stage while bellowing the notes he had been given, was infinitely more interesting than the work itself.

Adams, who has called his concerto a “caffeinated” piece, uses sprawling language throughout its 30 plus minute running time.

From the revved-up orchestral opening, sound swirled, twisted and turned like waves over the sax, requiring every bit of range from McAllister, and quickly. Aside from a quasi-bluesy passage in the center of the thing, the piece maintained a mysterious, lurking and darting quality, McAllister wandering through the passages as someone on foot might explore a strange environs. The NWS remained remarkably on point with sharp detail, several soloists performing well throughout the high flying piece.

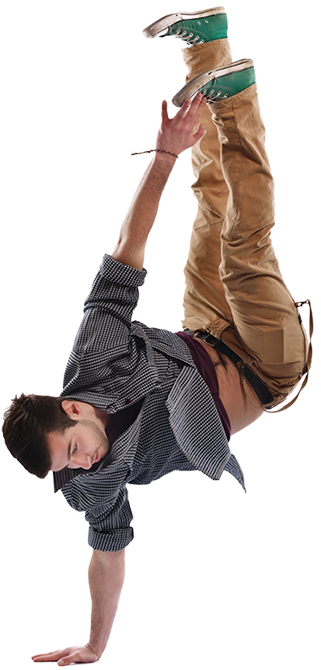

Timothy McAllister

McAllister is a strong player, both in tone and agility. He was so enjoyable, I crave to hear something more melodious from him. Tall and lean, he moved like a dancer as he played, asymmetrically in sync with the music.

The entire concerto remained in an agitated state. It serves well to agitate an audience. However, some resolution to the agitation serves both the composer and the listener. When the entire work is restless…well, that is certainly not everyone’s cup o’ tea. Hard to imagine anyone downloading this one from iTunes once they got home.

Someone unfamiliar with the work of Henri Matisse might decide at first glance that his overlapping paper panels, color combinations, and jellyfish and seaweed cutouts, are the creations of a preschooler with access to a pair of scissors, some paint and paper. Closer inspection, of course, turns to appreciation and the observer into a fan.

Something similar happened when listening to Andrew Norman’s Try, except that appreciation for his composition remains elusive.

The casually dressed Norman, who was present for this performance, mentioned that he “likes to push players to their limits and bring them to the verge of playability.” If this is what he wanted to accomplish with this piece, he succeeded. However, he didn’t succeed at much else.

Jumping out of an airplane at 10,000 feet playing your instrument might serve the same purpose. But to what accomplishment?

Norman indicated that he was happy that “he felt he didn’t have to get the piece right.” That’s usually a good strategy during the developmental stages of a new work, but certainly a questionable goal for the completed composition.

Where there isn’t much in the way of melody, harmony and rhythm, there isn’t much in the way of music either. Notwithstanding, the paired down ensemble of NWS players handled their chaotic assignments well.

The title, Try, might have several meanings: perhaps it is a dare to the musicians to “try” to navigate the notes as written, or, more likely, it refers to the piano “trying” to express itself which it attempts on several occasions and finally did by the end of the piece.

After the piano played the first two notes, boom, we are plunged into the fray as the powerful ensemble jumped the piano. The wild and madcap sound continued and the piano tried again to emerge with what might be a melody, and again was quickly chastised. Strings glistened, screamed and swarmed, winds remained in a frenzy, percussion pounded, the brass kept punching, and the piano undaunted, kept trying.

What might have proven to be an interesting musical conceit, that is, the piano pushing back and finally taming the beast with a fine melody, turned out to be only a few sophomoric piano arpeggios coagulating into basic chords to resolve the chaos – void of any substantive motif to satisfy the listener.

The applause rang of obligation rather than appreciation.

The evening’s conclusion – Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements – brought the crowd home, not only by its depth of melody but by having its context set in WWII. As Adams pointed out, the “fantastic mix of alternating major and minor keys made for an amazing brew.”

Stravinsky was notorious for avoiding the classical symphonic form, yet this one smacked well of symphony.

The big opening painted images of war, agitated with booming percussion trying to find its way to a melody. There was plenty of sound to create looming horror and subtle menace as well as an optimistic bounce. The flute (Emma Gerstein) took flight on a bouncy bed of strings during The Andante—Interlude (second movement). The harp (Julia Coronelli) further softened the mood, the reeds (John Upton playing oboe and Thomas Fleming playing bassoon) and flute took turns with a lilting melody. The sections and players got busy in the third movement; the running bottoms and sudden bursts, poking trumpets, and steadily advancing orchestra, bloomed into a final persuasive chord.

The stylish and gracious Adams recognized all the soloists and served up lively anecdotes between the pieces. The New World Center is a premium hall and the NWS players sounded tremendous in it.

MAIN MENU

MAIN MENU